Transforming snakebite treatment

to address a critical gap

There is a significant unmet need for snakebite treatment in the US and around the world.

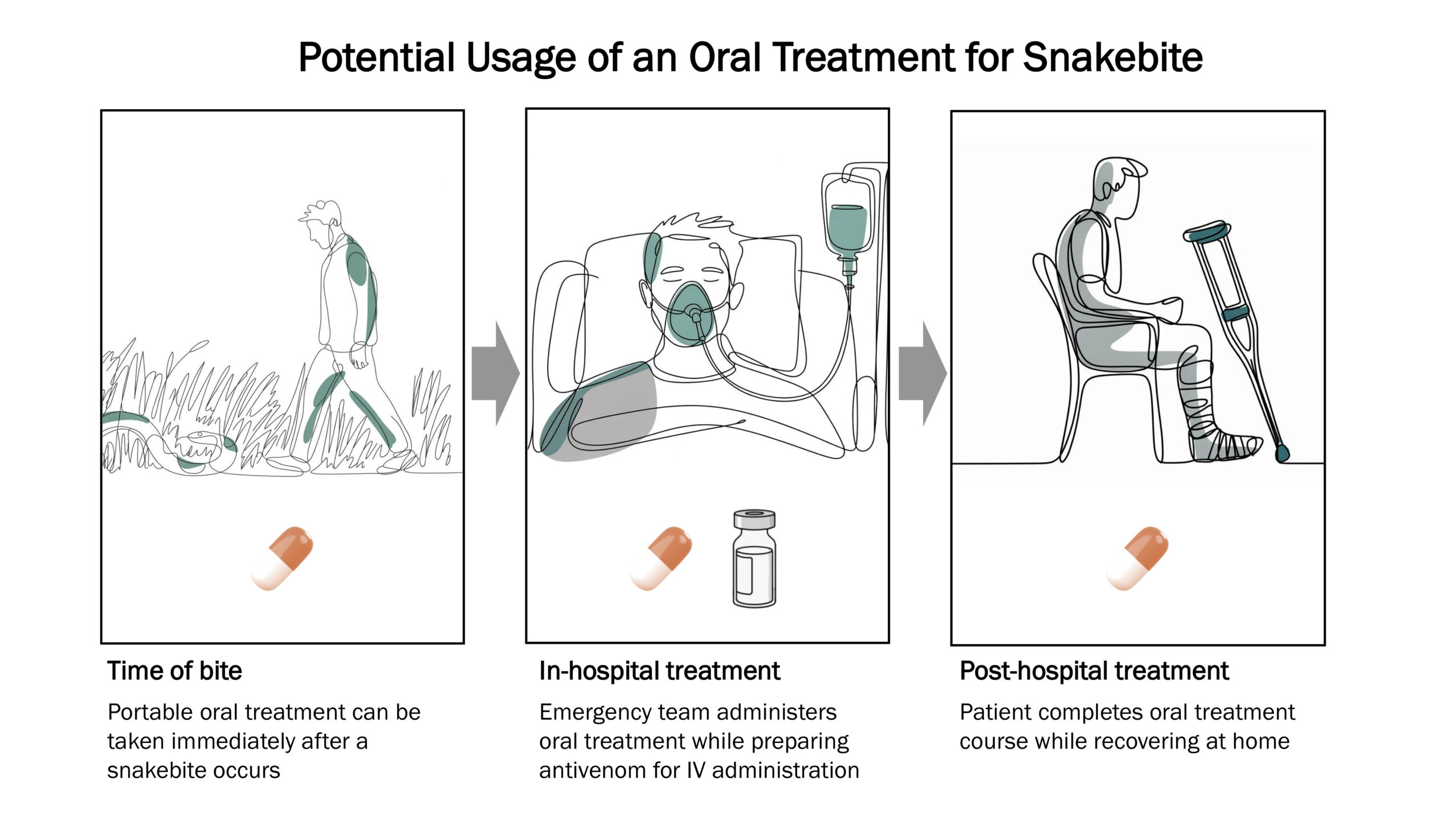

The current standard of care, which was developed more than 100 years ago, is antivenom once a snakebite victim reaches a hospital. However, for the 75% of snakebite deaths that occur prior to hospital arrival, hospital-based treatments are too late.1 Further, for snakebite, “time is tissue.” Every minute elapsed between the bite and initiation of treatment allows venom toxins to cause more damage—adding to the time needed for recovery and the risk of permanent disability.

Ophirex is pursuing a new approach to treating snakebite: an oral treatment that can be easily taken before reaching a hospital. For the first time ever, this new scientific approach could allow snakebite victims to start care immediately after a snakebite occurs.

69%

of snakebite victims in Southeast Asia have limited access to antivenom2

12 hours

is how long it takes snakebite victims in remote regions of Africa and Asia to reach antivenom, allowing a dangerous amount of time to pass3-7

Many

venomous snakes do not have a well-matched antivenom, leaving many victims with limited treatment options even if they reach a hospital in time8-10

A small molecule approach

to treating snakebite

Ophirex is developing varespladib, an inhibitor of sPLA2, a class of toxins that is present in the venom of more than 95% of snake species. Varespladib is a small molecule that can be administered orally. This is in contrast to antivenoms, which are biologics (polyclonal antibodies) that require administration through an IV. The snake species providing venoms used to immunize horses and sheep must be similar to the snake species that bit the patient in order for the antivenom to be effective.

Due to its mechanism of action, varespladib is expected to rapidly neutralize sPLA2 from any venomous snake, and an oral delivery method will fill a critical treatment gap.

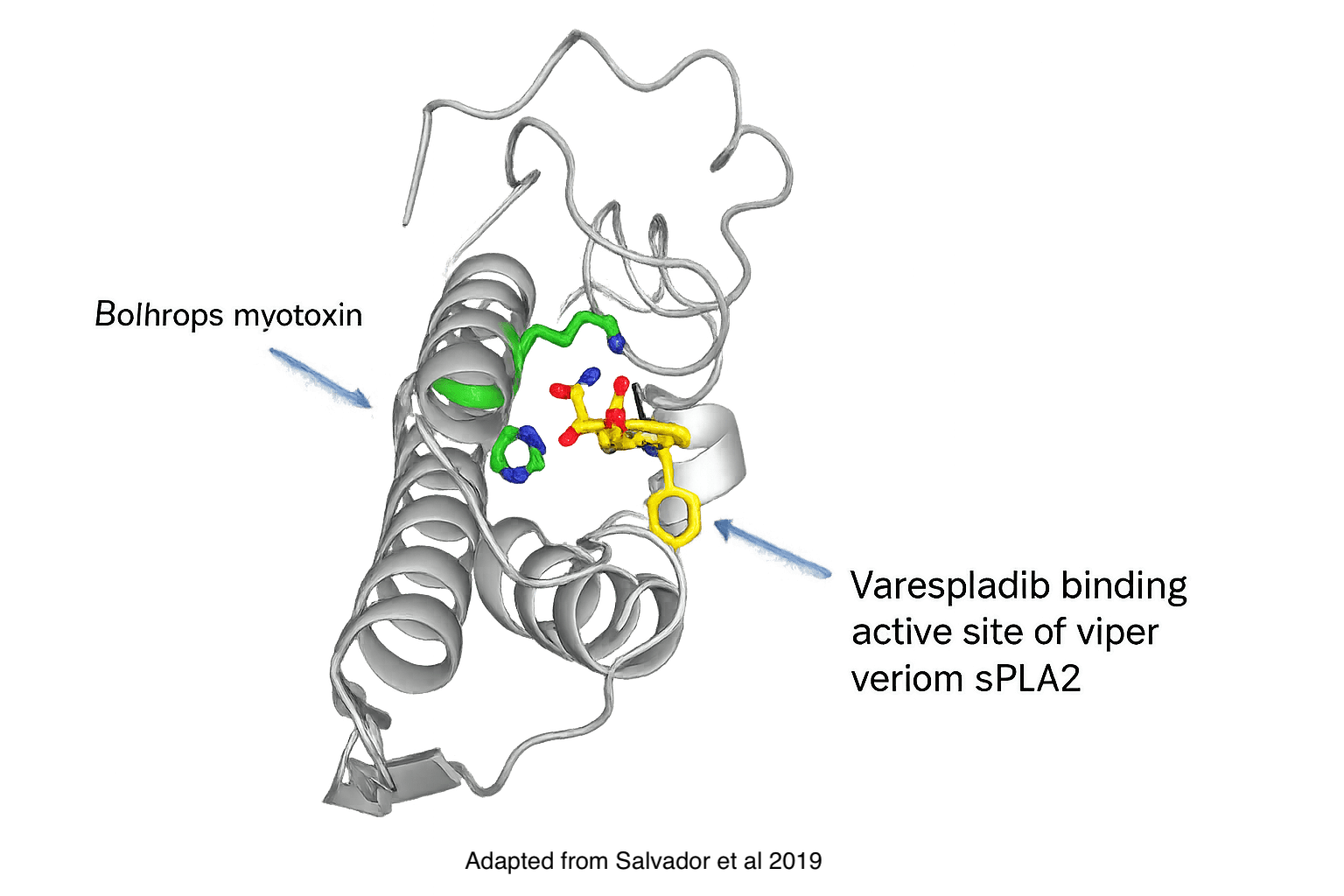

A novel mechanism of action

to treat snakebite

Varespladib is an effective inhibitor of snake venom sPLA2, a key driver of toxicity in snakebite envenomation.

Varespladib binds to a highly-conserved active site within the sPLA2 enzyme, acting like a wedge that blocks sPLA2 activity. By neutralizing sPLA2, varespladib helps prevent the cascade of downstream toxic effects triggered by venom.

Because sPLA2 is present in the venom of more than 95% of snake species and contributes significantly to venom-induced lethality and morbidity, inhibiting this target offers a broad-spectrum strategy for reducing the risk of severe outcomes following snakebite.

Ophirex has studied varespladib for snakebite envenomation in clinical trials as well as in animal studies. Pre-clinical results have shown that varespladib can reverse paralysis and restore blood clotting.

“In snakebite treatment, the sooner that you can get therapy started, the faster you’ll be able to stop ongoing injury from the toxins, and the better the outcome will be.”

Selected publications from the field

Top Image Adapted from Figure 6 in: Escalante T, Ortiz N, Rucavado A, Sanchez EF, Richardson M, Fox JW, et al. (2011) Role of Collagens and Perlecan in Microvascular Stability: Exploring the Mechanism of Capillary Vessel Damage by Snake Venom Metalloproteinases. PLoS ONE 6(12): e28017. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0028017. Licensed under CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/). Arrows removed for clarity and image quality and color is adjusted and enhanced using AI

Citations

- Mohapatra B, Warrell DA, Suraweera W, et al. Snakebite mortality in India: a nationally representative mortality survey. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011;5(4):e1018. Published 2011 Apr 12. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0001018

- Patikorn C, Blessmann J, Nwe MT, et al. Estimating economic and disease burden of snakebite in ASEAN countries using a decision analytic model. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2022;16(9):e0010775. Published 2022 Sep 28. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0010775

- Iliyasu, G., Tiamiyu, A.B., Daiyab, F.M., Tambuwal, S.H., Habib, Z.G. and Habib, A.G., 2015. Effect of distance and delay in access to care on outcome of snakebite in rural north-eastern Nigeria. Rural and remote health, 15(4), pp.76-81.

- Mahendra M, Mujtaba M, Mohan CN, Ramaiah M. Study of Delayed Treatment Perspective of Snake Bites and Their Long-Term Effects in a Tertiary Care Hospital in Balgalkot District of Karnataka. APIK Journal of Internal Medicine. 2021;9(3):153-158. doi:https://doi.org/10.4103/ajim.ajim_78_20

- Patikorn C, Ismail AK, Abidin SAZ, et al. Situation of snakebite, antivenom market and access to antivenoms in ASEAN countries. BMJ Glob Health. 2022;7(3):e007639. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2021-007639

- Aga AM, Mulugeta D, Motuma A, et al. Snakebite cases and treatment outcomes in the Afar region, Ethiopia: a retrospective and prospective study approach. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2025;119(9):1047-1054. doi:10.1093/trstmh/traf043

- Cristino JS, Salazar GM, Machado VA, et al. A painful journey to antivenom: The therapeutic itinerary of snakebite patients in the Brazilian Amazon (The QUALISnake Study). PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2021;15(3):e0009245. Published 2021 Mar 4. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0009245

- Warrell DA, Williams DJ. Clinical aspects of snakebite envenoming and Its Treatment in Low-Resource Settings. Lancet. 2023;401(10385):1382-1398. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00002-8

- Senji Laxme RR, Khochare S, de Souza HF, et al. Beyond the 'big four': Venom profiling of the medically important yet neglected Indian snakes reveals disturbing antivenom deficiencies. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13(12):e0007899. Published 2019 Dec 5. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0007899

- Rogalski A, Soerensen C, Op den Brouw B, et al. Differential procoagulant effects of saw-scaled viper (Serpentes: Viperidae: Echis) snake venoms on human plasma and the narrow taxonomic ranges of antivenom efficacies. Toxicol Lett. 2017;280:159-170. doi:10.1016/j.toxlet.2017.08.020

- Tasoulis T, Isbister GK. A Review and Database of Snake Venom Proteomes. Toxins (Basel). 2017;9(9):290. Published 2017 Sep 18. doi:10.3390/toxins9090290