Snakebite is a major global

public health concern

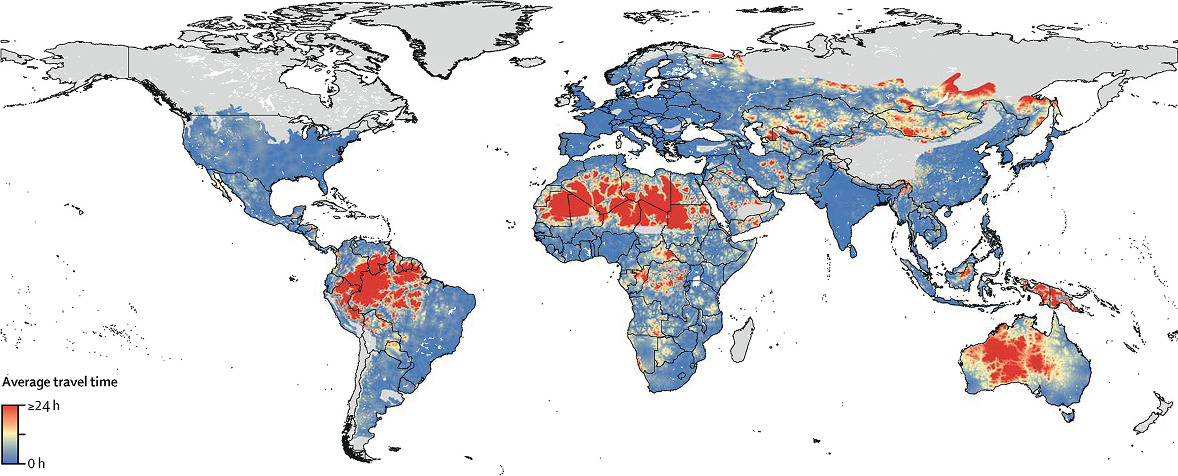

Average travel time to nearest major city for populations living within snake ranges. The light grey areas represent locations without medically important venomous snake species.

Source: Longbottom J, Shearer FM, Devine M, et al. Vulnerability to snakebite envenoming: a global mapping of hotspots. Lancet. 2018;392(10148):673-684. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31224-8.

Globally, 4-5 million people experience snakebite envenomation each year,1 and 125,000 people around the world die from snakebite each year. 2 There are three times as many amputations and permanent disabilities as deaths.1, 3

Every continent except Antarctica has venomous snakes, with the highest burden of snakebite occurring in the middle latitudes.4,5 India alone has approximately 50,000 snakebite deaths each year.6

Antivenom is expensive, and small local clinics often don’t stock the antivenom that victims of snakebite need. This means that, especially in rural areas, a dangerous amount of time may pass between a snakebite and treatment. In remote regions in Africa, Asia, and South America a patient may travel 12 hours or more to reach a hospital with antivenom.7, 8, 9, 10, 11

Venomous snakes are found in

nearly all 50 states

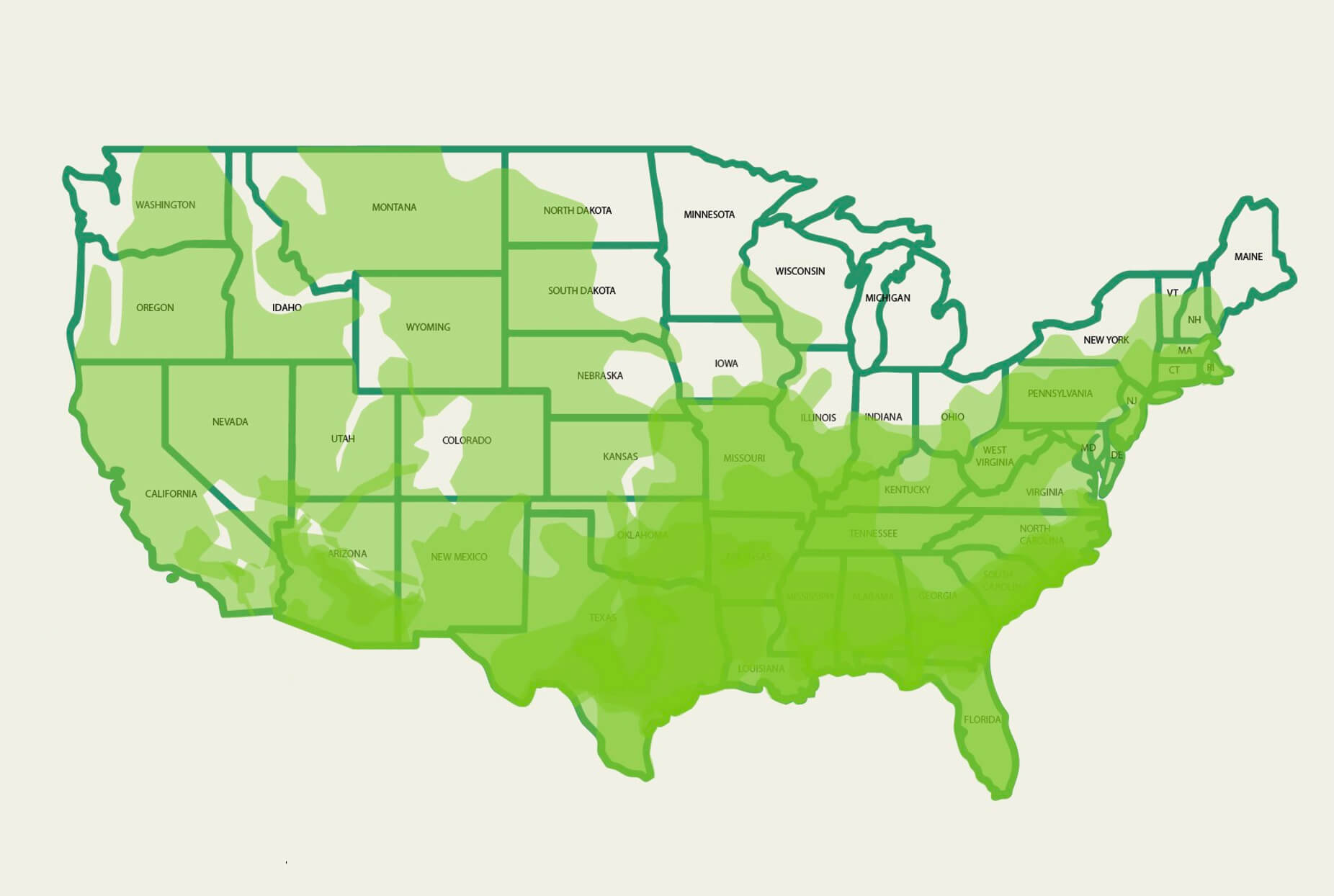

Map shows distribution of WHO Category 1 Pit Vipers and Eastern Coral Snake.

Source: Rautsaw RM, Jiménez-Velázquez G, Hofmann EP, et al. VenomMaps: Updated species distribution maps and models for New World pitvipers (Viperidae: Crotalinae). Scientific Data. 2022;9(1). doi:10.1038/s41597-022-01323-4.

An estimated 10,000 people are bitten by venomous snakes annually in the US.15 Nearly one quarter of snakebites in the U.S. occur in children.16, 17 U.S. snakebites frequently cause severe pain and tissue damage. Some patients have persistent disability as a result of the bite.

Before modern medical care and antivenom, U.S. snakebite mortality was about 10%.18 Today, snakebites still kill 5 to 10 people a year in the U.S.15 More than 30% of U.S. patients report persistent pain, edema, or functional impairment 3 months after envenoming.19 The cost of antivenom is also a concern for both patients and physicians.20

The risk of venomous snakebite increases during the summer, with 84% of cases occurring in warmer months.20 Snakes are commonly found along hiking trails, around homes near wooded areas or tall grasses, near rivers and lakes, and in the deserts of the Southwest. Urban and suburban expansion has also increased human–snake encounters.

Venomous snakebite is treated with antivenom, but not all emergency rooms stock antivenom, and it can be difficult to determine the ones that do.20 Factors such as cost and the frequency of venomous snakebites in an area play a role in a hospital’s decision to stock antivenom. This presents a risk for people who need to travel long distances to access antivenom following a snakebite, since treatment should be administered as soon as possible.

Rattlesnakes: Rattlesnakes are the most common venomous snake in the U.S. They are often found sunning near logs, boulders or open areas across mountains, prairies, and deserts. While rattlesnakes are known for the distinct sound they make, some stay silent when threatened.

Citations

- Afroz A, Siddiquea BN, Chowdhury HA, Jackson TN, Watt AD. Snakebite envenoming: A systematic review and meta-analysis of global morbidity and mortality. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2024;18(4):e0012080. Published 2024 Apr 4. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0012080

- Warrell DA, Williams DJ. Clinical aspects of snakebite envenoming and Its Treatment in Low-Resource Settings. Lancet. 2023;401(10385):1382-1398. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00002-8

- Waiddyanatha S, Silva A, Siribaddana S, Isbister GK. Long-term Effects of Snake Envenoming. Toxins (Basel). 2019;11(4):193. Published 2019 Mar 31. doi:10.3390/toxins11040193

- Rautsaw RM, Jiménez-Velázquez G, Hofmann EP, et al. VenomMaps: Updated species distribution maps and models for New World pitvipers (Viperidae: Crotalinae). Sci Data. 2022;9(1):232. Published 2022 May 25. doi:10.1038/s41597-022-01323-4

- Longbottom J, Shearer FM, Devine M, et al. Vulnerability to snakebite envenoming: a global mapping of hotspots. Lancet. 2018;392(10148):673-684. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31224-8

- Mohapatra B, Warrell DA, Suraweera W, et al. Snakebite mortality in India: a nationally representative mortality survey. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011;5(4):e1018. Published 2011 Apr 12. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0001018

- Iliyasu, G., Tiamiyu, A.B., Daiyab, F.M., Tambuwal, S.H., Habib, Z.G. and Habib, A.G., 2015. Effect of distance and delay in access to care on outcome of snakebite in rural north-eastern Nigeria. Rural and remote health, 15(4), pp.76-81.

- Mahendra M, Mujtaba M, Mohan CN, Ramaiah M. Study of Delayed Treatment Perspective of Snake Bites and Their Long-Term Effects in a Tertiary Care Hospital in Balgalkot District of Karnataka. APIK Journal of Internal Medicine. 2021;9(3):153-158. doi:https://doi.org/10.4103/ajim.ajim_78_20

- Patikorn C, Ismail AK, Abidin SAZ, et al. Situation of snakebite, antivenom market and access to antivenoms in ASEAN countries. BMJ Glob Health. 2022;7(3):e007639. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2021-007639

- Aga AM, Mulugeta D, Motuma A, et al. Snakebite cases and treatment outcomes in the Afar region, Ethiopia: a retrospective and prospective study approach. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2025;119(9):1047-1054. doi:10.1093/trstmh/traf043

- Cristino JS, Salazar GM, Machado VA, et al. A painful journey to antivenom: The therapeutic itinerary of snakebite patients in the Brazilian Amazon (The QUALISnake Study). PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2021;15(3):e0009245. Published 2021 Mar 4. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0009245

- Chippaux, J.P., 2011. Estimate of the burden of snakebites in sub-Saharan Africa: a meta-analytic approach. Toxicon, 57(4), pp.586-599.

- Kasturiratne A, Wickremasinghe AR, de Silva N, et al. The global burden of snakebite: a literature analysis and modelling based on regional estimates of envenoming and deaths. PLoS Med. 2008;5(11):e218. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0050218

- Chippaux J-P (2017) Incidence and mortality due to snakebite in the Americas. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 11(6): e0005662. https://doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005662

- Langley R, Haskell MG, Hareza D, King K. Fatal and Nonfatal Snakebite Injuries Reported in the United States. South Med J. 2020;113(10):514-519. doi:10.14423/SMJ.0000000000001156

- Schulte J, Domanski K, Smith EA, Menendez A, Kleinschmidt KC, Roth BA. Childhood Victims of Snakebites: 2000-2013. Pediatrics. 2016;138(5):e20160491. doi:10.1542/peds.2016-0491

- Tadros A, Sharon M, Davis S, Quedado K, Marple E. Emergency Department Visits by Pediatric Patients for Snakebites. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2022;38(6):279-282. doi:10.1097/PEC.0000000000002725

- Gold BS, Dart RC, Barish RA. Bites of Venomous Snakes. New England Journal of Medicine. 2002;347(5):347-356. doi:https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmra013477

- Smelski GT, Guthrie AM, Axon DR, Shirazi FM, Walter FG, Gerardo CJ. Long-Term Clinical Outcomes of Rattlesnake Envenomation in Arizona Following Treatment With Crofab vs Anavip: A Retrospective Observational Study. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2025;6(4):100207. Published 2025 Jun 12. doi:10.1016/j.acepjo.2025.100207

- Tupetz A, Barcenas LK, Phillips AJ, Vissoci JRN, Gerardo CJ. BITES study: A qualitative analysis among emergency medicine physicians on snake envenomation management practices. PLoS One. 2022;17(1):e0262215. Published 2022 Jan 7. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0262215

- Thornton S, Darracq M. Epidemiology and Characteristics of North American Crotalid Bites Reported to the National Poison Data System 2006-2020. South Med J. 2022;115(12):907-912. doi:10.14423/SMJ.0000000000001484